The Masaryk Case: the Murder of Democracy in Czechoslovakia * * * *

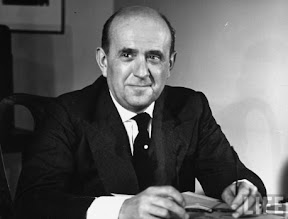

World War II altered forever Americans "world-view" and how we view international conflicts and war. Though easily forgotten, Americans themselves were of an "isolationist" view before WWII. A poll in Dec. 25, 1938 found Americans 6 to 1 against sending troops to Europe; "It's not our business!" was the universal view. Munich 1938 was the beginning of a change[2] -- because it was such a terrible betrayal and because of Jan Masaryk's eloquent writings and speeches on his country's plight. Today few outside the Czech Republic and Slovakia would recognize the name of Jan Masaryk, but in 1938 and during WWII, he was a well-known diplomat and radio voice in America and Britain. A BBC radio address by Jan Masaryk on August 27, 1939 as Germany threatens to invade Poland:

World War II altered forever Americans "world-view" and how we view international conflicts and war. Though easily forgotten, Americans themselves were of an "isolationist" view before WWII. A poll in Dec. 25, 1938 found Americans 6 to 1 against sending troops to Europe; "It's not our business!" was the universal view. Munich 1938 was the beginning of a change[2] -- because it was such a terrible betrayal and because of Jan Masaryk's eloquent writings and speeches on his country's plight. Today few outside the Czech Republic and Slovakia would recognize the name of Jan Masaryk, but in 1938 and during WWII, he was a well-known diplomat and radio voice in America and Britain. A BBC radio address by Jan Masaryk on August 27, 1939 as Germany threatens to invade Poland: Czech Ambassador In London On Poland Situation – 1939-08-27 BBC

Written by an American journalist, this book tells the story of the events of those tumultuous years and the events and people surrounding his death. The interviews and research for the book took place during the summer and autumn of 1968 -- a rare window during which a Western journalist could travel and talk with people in Czechoslovakia. During the 1950s, the Iron Curtain was an Iron Wall for people outside the communist bloc. Travel into the communist bloc from the West was difficult and once inside, speaking with people was next to impossible because the consequences for speaking with a Westerner were harsh. No one spoke freely except to their closest and most trusted friends. It was a cold gray never ending winter. But then in the summer of 1968, a miraculous thawing, the Prague Spring, occurred in Czechoslovakia. Restrictions on speech were lifted and for a brief few months the Czechoslovaks were free to speak out. During that summer of 1968, an American journalist went to Czechoslovakia to investigate one of this great intrigues of end of World War II, the death of Jan Masaryk. Her book, "The Masaryk Case", is about what she discovered during her investigations and interviews, but much more than that, it is a rare glimpse into the communist bloc during the middle of the Cold War.

The central character, Jan Masaryk was the son of Tomas Masaryk. Tomas Masaryk founded the Czechoslovak democracy after WWI and was the first Czechoslovak president. At the time, that is during WWI in the 1920s, Czechoslovakia was in some ways the adopted child of the United States. The U.S. was instrumental in helping guide Czechoslovakia to democracy after WWI, and the first Czechoslovak constitution was signed in New York City. The Masaryk family had a number of connections to America including close relatives there. During the 1940s, the time during which much of the story in this takes place, Tomas Masaryk was already revered as a great statesman and leader. To the Czechoslovaks, he was (and still is) revered like George Washington or Abraham Lincoln are revered in the U.S.

His son, Jan, however was an incorrigible playboy with seemingly none of the talents of his great father. In Jan's late teens, he was sent by his family to America to make his own way in life -- and presumably teach him a few lessons. Jan lived 10 years in America, working in menial clerk jobs. In his late 20s, Jan returned home and was promptly drafted into WWI and served in Austria. After the war, Jan continued his playboy ways but began to assume some of the responsibilities foisted upon him by his lineage as the son of a national hero. He took a position as a diplomat in the government of Benes, the 2nd Czechoslovak president. Jan perhaps would have remained just the playboy son of Tomas Masaryk in the Czechoslovak national memory if it were not for Munich 1938 and its aftermath. As it was, he became the embodiment of the tragedy of Czechoslovakia in WWII, and his death/murder became an allegory for the murder and betrayal of Czechoslovakia.

Munich 1938. In one of the 20th century's great betrayals, William Chamberlain -- the prime minister of Britain at the time -- sacrificed Britain's ally, Czechoslovakia, to Hitler in an attempt to appease Hitler and preserve peace. Czechoslovakia's defenses along her western border were handed over to Germany and the Czechoslovaks were ordered not to resist. Once it became clear that Czechoslovakia's allies (those with whom she had mutual military assistance treaties), England, France and Russia, would not come to her aid, she was quickly dismembered by her neighbors. Four months after Munich, she was an occupied country. Her resources were sent to Germany, her industry was serving Germany, and her population was enslaved to serve the Reich. One of the most industrialized countries before the war, she would go on to become the arms factory for Germany during the war.

Jan Masaryk's was serving as a diplomat in London at the time, and he became the voice of Czechoslovakia's tragedy. He spoke English fluently and without accent, and gave many radio speeches during that time. From one of his radio addresses after Munich:

Text of the radio address in the video above: “You will see things happening in my little country diametrically opposed to everything my father stood for and I humbly but proudly stand for today. And I beg of you to understand it. My people were terribly hurt. They were suddenly told, with very little ceremony, that they must shut up and give up. Otherwise – it was a terrible otherwise… This is another job for the historians. I am not really complaining. I am just trying to explain in simple words what went on in the heart of the simple Czech and Slovak, man and woman, who trusted their allies and their friends and quite suddenly found themselves alone, bereft and destitute in a blizzard of harshness.”

This book was fascinating to me because it told about the life of Jan Masaryk and the crucial pre- and post-WWII years involving Czechoslovakia. But it also tells a fascinating story about the Czechoslovak mindset in the late 1960s and about how people processed the war and the post-war betrayals and upheavals. The thing that comes up repeatedly is how Czechoslovaks who lived through the war and post-war period were trying deal with their own feelings of complicity in their downfall. The people she interviews have a sense that the Czechoslovaks did not really resist the Germans. In the sense that there was no great partisan movement as in some other Slavic countries, e.g. Poland and Belarus. This is not to say there weren't partisans and that there are not examples of courageous resistance, but the Czechs feel that they tended to take the easier (and less lethal) ways out. Upon invasion, the government quickly aligned with Germany--true the alternative was terrible. Later it aligned with Russia--again the alternative was terrible.

But they Czechs she interviews express a lurking sense that their country and they themselves were always making a Faustian bargain with some devil or another. On the other hand, the Czech Republic was the only German-annexed country that did not provide troops for the Reich Army. Every other annexed country did: Romania, Slovakia, Hungary, Austria and Poland. The Czechoslovaks that the journalists interviews bring this up themselves and are obviously trying to process all these conflicting views of themselves. They seem large unsuccessful in this attempt.

--EEH, May 19, 2010

________________________________________________

Radio Prague article about the 60th anniversary

http://www.radio.cz/en/article/101758

Radio broadcasts

http://www.radio.cz/en/article/11875

http://archiv.radio.cz/english/talking/16-11-99.html

[1] Change in the official verdict: murder

http://www.radio.cz/en/article/49113

[2] A sea change in public opinion about strict neutrality (including no arms shipments to England) occurred after the Munich agreement. This change in public opinion is reviewed from the perspective of late 1939 in the article:

Influences of World Events on U.S. "Neutrality" Opinion, Philip E. Jacob, The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Mar., 1940), pp. 48-65. In a short period of 8 weeks public opinion switched from high levels of support for complete neutrality to the opinion that the US should support England and ship weapons to England and France to resist Germany. This change in public opinion did not however extend to sending troops. Resistance to sending troops remained very high--ca. 95% against and ca 80% against EVEN if England and France looked like they would lose. After Munich, this erodes a bit to 84% and 54% (if E and F are losing). But by the end of 1939, opinion switched back to extremely high resistance to sending troops (unless the US is attacked). However, the change in public opinion concerning arm shipments to England did have an effect. The arms embargo that prevented weapons from being sold to England was lifted on November 4, 1939 (via modification of the Neutrality Act). For reference, Germany invaded Poland on Sept 1, 1939 and England declared war on Germany on Sept 3, 1939.

Labels: Czech

<< Home